My first business trip – to Cairo, in 1975

I wasn’t expecting to find my boss waiting for me at Heathrow when I arrived back in London. Even less the first words he spoke to me. “You’re on your own? Where are all the students? The bus is waiting outside.” Oh heavens, I thought, with a sinking heart – not only had he not told me what I was getting into, but his overseas “partner” had actually hoodwinked him…

That was a memorable trip in so many ways. I learnt so much, things I’ve never forgotten. Books can only tell you so much – lessons are much more effective when learnt the hard way!

First, a little background. I left university at a time of economic adversity when there weren’t many good jobs to be had. I took what I could get – what I now call a series of “odd jobs”. All valuable experience, though. This one was working for a slightly dubious school of English as a foreign language in Central London. Despite my youth and lack of formal teaching experience, I enjoyed the elevated title of Principal. Not because I was the top dog, you understand – now I think about it, I was more the top dogsbody. No, my qualification for the job was that I was white, British, well-spoken, wore a suit and tended not to panic when officialdom turned up for inspections or, occasionally, to retrieve students who had overstayed their visas or committed some misdemeanour.

In the spring of 1975, an Egyptian business owner – a travel agent – convinced my boss that they could do a roaring trade in bringing young people to study English in London. There were no shortage of applicants, said the Egyptian, but to travel they needed visas, and to get those they needed an expert opinion that they would benefit from studying in England. Thus, supposedly as a reward for my hard work, I was despatched to Cairo to help recruit studentwsPart of my mission was to deliver such opinions.

Back in 1975, not only was there no email, even making international telephone calls (at least from Egypt) was a nightmare; one had to go to the Post Office, wait in a long queue, suffer dead connections and, when successful, pay a massive bill. All that meant that sending one’s employee overseas – with not much chance of further contact before they returned – required my boss to have large doses of trust, faith and hope.

I was thrilled, of course. Thrilled to be trusted with such a significant business opportunity. Even more thrilled to get to visit such an exotic country at company expense!

I set off on April 13 via Beirut. A memorable date, because the civil war in Lebanon broke out while I was in flight from London! The passengers and crew were told about it by the pilot over the intercom only once we had landed. Another memory is that I spent the journey composing a letter to my prospective father-in-law, handwritten of course, in my rudimentary Spanish, requesting the hand of his daughter in marriage, but I digress (and give away my age).

Having been told so much about Beirut by various friends, I was looking forward to breaking the journey and visiting. However, the hostilities, all I got to see was the airport terminal, where I spent a very long time waiting for the first available seat on a connection to Cairo. As you might imagine, it seemed that everyone who could was getting out.

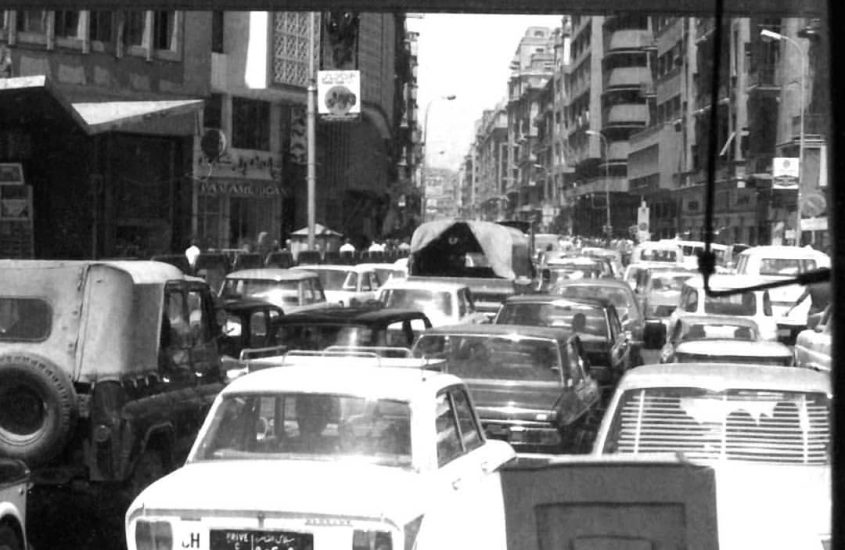

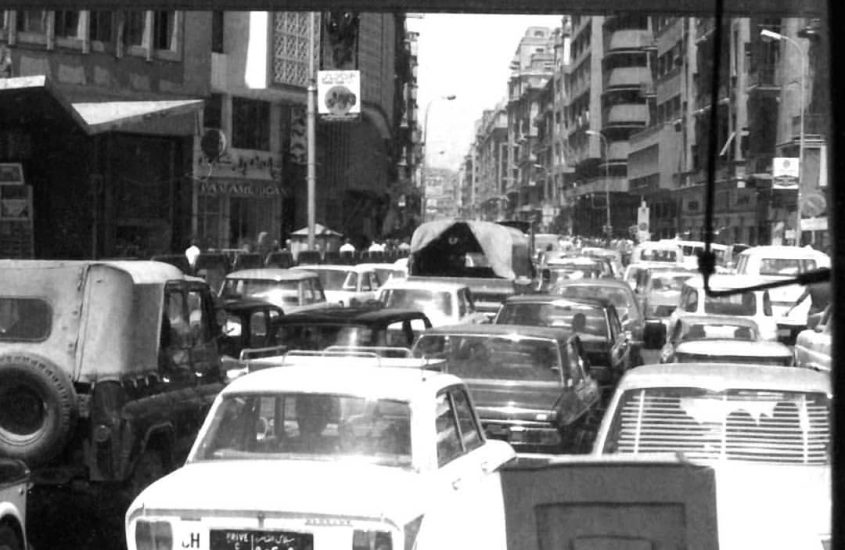

Somehow or other, my boss’s new partner and my contact, Sami, had been told about my new flight details and met me at the airport. Admirers surrounded his new-ish car, a Fiat 124, so I immediately discovered that in Cairo in 1975, anything better than a wreck was a status symbol. Once we drove into the city, I also discovered Cairo traffic. It was already arguably the worst in the world, and it’s only got worse since.

My boss had met Sami in London. He’d impressed him; he said he was from a rich family, with many businesses including a travel agency, and he’d proposed an arrangement that was supposed to be mutually advantageous, with him sourcing students from Egypt for my boss’s schools of English language in London, so he would get commission from both the tickets he sold them and their course fees. My boss clearly believed that the students would come in droves, and I, young and naïve, accepted what I was told.

Sami was certainly well-off, and he was young and fun-loving. He delivered me to a posh-looking hotel on the Nile Corniche, where he seemed to know everyone. My room certainly wasn’t posh, though. I remember it as being on the top floor (no lift), at the back, overlooking a junk yard and with the nearest bathroom being down a long unlit corridor. Fortunately I didn’t have to spend much time on it.

Sami was eager to show me the sights. What an adventure! Sami took me everywhere and paid for everything. Even though Egypt in those days was cheap by British standards, that was just as well, as my heady job title didn’t come with a matching salary.

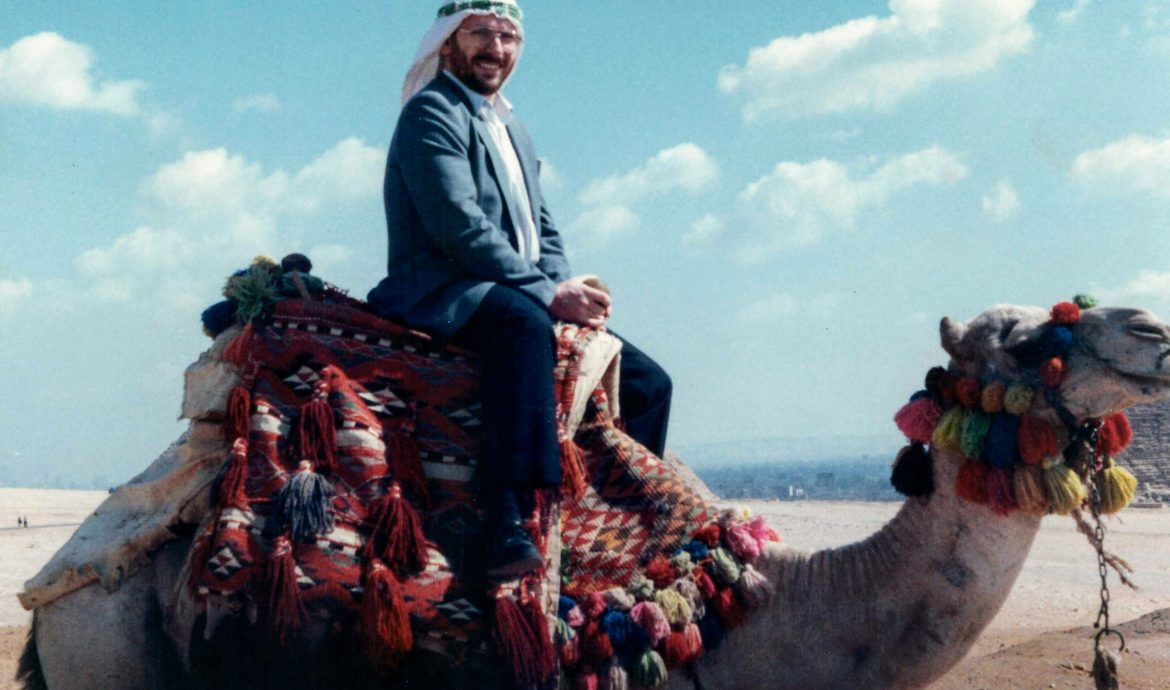

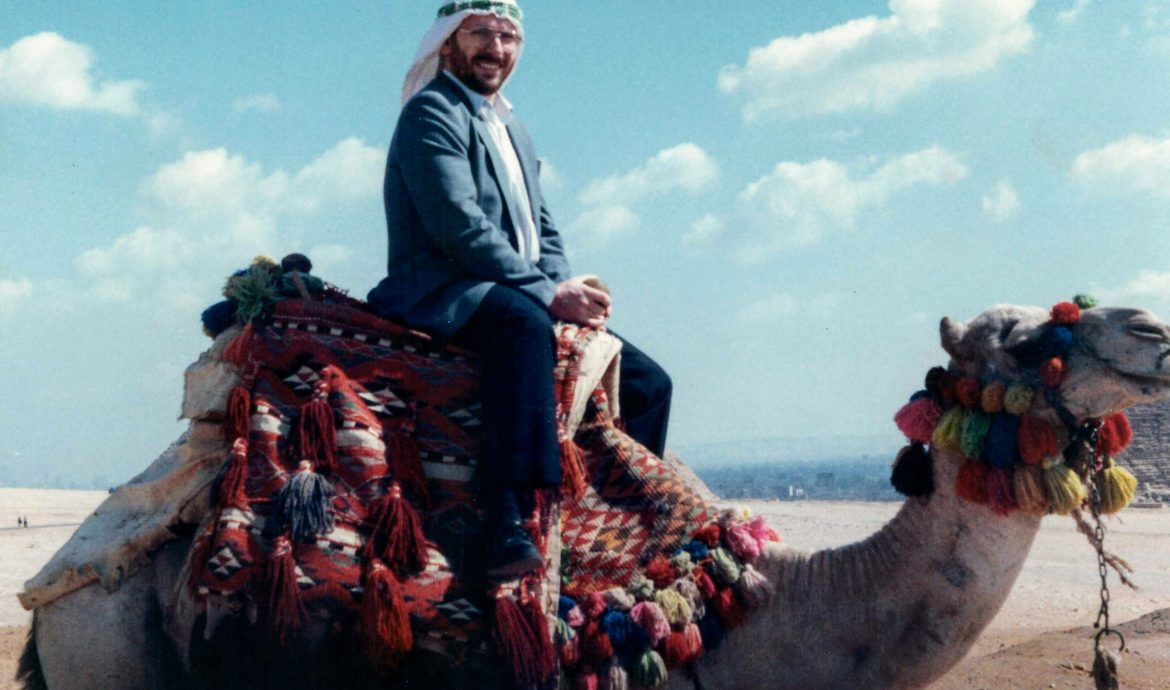

Of course, we started with the Pyramids and the Sphinx. So close to the city, yet surrounded by desert. I’ve been back a few times, and still find it awe-inspiring. There were few tourists then, which meant that no sooner were we out of the car than camel drivers selling rides surrounded us. Sami picked one and bargained away. This was my Lawrence of Arabia moment! My agility and posture is about as ungainly as a camel’s, but with a lot of pushing and shoving I got up there, and then “enjoyed” a quarter of an hour being rocked from side to side and up and down as we walked around one of the pyramids.

Second on my list was the Cairo Museum. I’d been amazed by the Tutankhamen Exhibition in the British Museum when my parents too me there – I must have been about ten – and I wanted to see more. It was so disappointing. Yes, there were lots of mummies, lots of stones, lots of scrolls, but everything was deeply layered with dust. The glass in display cases might as well have been frosted. And it was quiet! I was almost on my own there. Since then, of course, it’s been modernised and everything is now displayed in pristine, dust-free condition.

What most fascinated me was one thing I hadn’t expected. The market. It seemed that the whole of central Cairo was a market, but the main souk was something else. Straight out of the Arabian Nights, a childhood favourite book. As if nothing had changed in a thousand years. Permanently crowded, almost everyone in Arab dress, stallholders hassling anyone who dared stop to glance at their wares. The noise! The smells! I might well have been scared – especially of getting lost in the never-ending warren of tunnels – if Sami had not been guiding me, greeting half the population as if they were best friends, bargaining along the way. In the process we drank countless small glasses of sickly sweet tea forced on us by shopkeepers. I lost my initial trepidation and have adored getting lost in markets the world over ever since.

The best and the worst was the food. Foul Medames aren’t unpleasant women, but mashed beans mixed with oil and spices, eaten like porridge and ubiquitous. Nice enough, very filling, but I quickly had enough of it. (If you want to try it, the recipe by my favourite food writer is here) Sami, who enjoyed snacking and had the physique to show for it, bought falafel wherever he saw it, which was on more or less every street corner. My favourite, which I have never tired of, was kofta kebabs – grilled skewers of minced lamb mixed with spices. The worst was what unhygienic street food did to my insides. I don’t think they had invented Imodium then.

A day and night trapped in my hotel room, hoping against hope that the occupants of the room opposite didn’t want the lavatory at the end of the corridor when I (frequently) did.

Recovered, Sami drove us back towards the pyramids for beer and belly-dancing at the Mena Oberoi, then by far the most opulent hotel in Cairo. A world apart, once through the gates there were gardens, pools and total quiet. But not in the restaurant. We drank bottle after bottle of beer, Sami enthusiastically encouraging me to stuff banknotes into the underwear of the dancers who gyrated in front of us. I found it very embarrassing.

What I didn’t see was students. I was so enamoured by being a tourist in Cairo that it took me a few days to remember that I was there to work. Even then, I had to ask him for three days running before he took me to his travel agency. Not at all what I had expected. To start with, it was buried deep in the bazaar. Once I saw it, I realised why he’d not been in any hurry to show me. It was more or less just a dingy room under an archway, with a shabby sign over it and a few faded airline posters on the walls.

That wasn’t unusual. In those days, most “shops” and “offices” in Cairo were basically just rooms with no shop window, just a shutter brought down at night to cover the frontage. There are still plenty like that (and in most developing countries), but it came as a shock to me. I knew it wasn’t what my boss would have been expecting, either. Not only did Sami, in his Savile Row suit, look entirely out of place there, but I couldn’t imagine it as a sales office for a respectable British language school. Or even an unrespectable one. Sami pointed to a tiny table at the back with a stool on either side and told that would be my “office”. A privileged position, as the pukka fan was right overhead.

I asked him where the customers – the students – were. “They will come,” he assured me. All the time I sat there, though, nobody came, even to buy a bus ticket (the only service the agency advertised on the board outside).

For two days, I didn’t press him. I was young, having a good time and, to be honest, in no hurry to do any work. Eventually, however, my conscience got the better of me, and I forced an answer from him. He told me he was waiting for my boss to send him money (he called it “the investment”) before he would start advertising for customers.

That really brought home to me I hadn’t asked enough questions before I left London. I probably hadn’t asked any. But, knowing my boss, I was almost certain that he wasn’t intending to send Sami any money in advance.

It took another couple of days for me to convince Sami to phone my boss. By then I’d been there nearly two weeks; I’d had a great time exploring, but had achieved nothing business-wise. Sami returned from the call office with the news that the money was coming, but he was postponing the student recruitment drive. I was to go home.

That didn’t prove to be as easy as it sounds. Whilst I had a return ticket, it was on MEA via Beirut, and by now they’d stopped flying because of the war. That prompted another discovery. Sami’s agency couldn’t issue me a replacement ticket. With any airline. They had no licence.

I can’t remember how Sami arranged it, but a few days later I found myself seated in the back row of an EgyptAir plane, headed to London, theoretically non-stop. For the first three or four hours we went nowhere. Sitting on the tarmac, in baking heat, with the plane doors open. The cabin crew eventually distributed bottles of water, but ran out three rows before they reached me. It was to be a dry flight in every sense of the expression. Then, less than an hour after take-off, the pilot announced that we would land at Athens to refuel. After that, there was a “technical” stop in Frankfurt. Hence, the journey took forever – and, although the crew came round with some sort of meal, I remember it being impossible to get a drink.

And so, eventually, to London, and, after a fraught time with customs, who wanted to open the hookah that I’d bought as a souvenir with a tin opener, the unexpected greeting from my boss. He claimed that the two-faced Sami had called him to say that my trip had been very successful and a lot of students had been recruited, who were all coming to London with me on the same plane. Which explains why he’d turned up with a coach. And, of course, why he blamed me.

From the perspective of my boss’s language school, the trip was entirely unsuccessful. However, I not only had a wonderful time but learnt some fundamentals of business that stood me in good stead over the rest of my career.

One, never believe that what your business “partner” tells one party is what they tell another (and, sometimes, don’t believe a single word they say).

Two, always insist on visiting a partner or supplier’s business operation for yourself before committing to anything or sending someone else.

Three, put everything you can in writing, signed by both parties in indelible ink if blood isn’t readily available.

Four, if you’re sending someone else on a mission, be sure that they know everything that you do about the initiative, however irrelevant it might seem.

Five, check out the political situation in the country you’re going to and any stopovers along the way (even if those countries are supposedly stable democracies).

But the most important thing I learnt on that trip, something that’s proved incredibly useful over the years, is how to bargain with traders in a market. Sami was a master of that. My first lessons in Negotiating Skills. Maybe that’s a suitable subject for another story, another day.

An abridged version of this article was previously posted on GrowInternational, the website that accompanies the podcast series I hosted in 2017-19